Vignettes

Vignettes

April 24, 2014

by Artaxerxes

I remember the day when the Mithraeum in Aquae Sulis caught fire.

“How many got out?” I asked.

Magnus turned to me. “What?”

I: “Did anyone escape?”

Magnus: “Only seven besides the courier of the sun, and three of those were musicians. Mehercle!”

Mehercle was right. We had lost a swathe of good—in some cases, very good—officers from the legion. We had to make sure that this did not happen again.

You have to remember that in those days policing was an infant science. But we followed best practices and, I like to think, we got results.

We drove the foreigners, the insane and the Christians out of town that same evening.

April 17, 2014

by Artaxerxes

In Caer Edin, we are told, lived a prince, long ago. He loved a princess, and she loved him: and the date for their marriage had been set. But she contrived to offend an enchanter in three bodies, and was sung into the body of a swan. He watched sadly as she flew away into the gathering evening, until she was just a dot in the sky, and then went and lost himself in wine.

Once he had got himself good and drunk, he got himself good and sober again: then for a year and a day he paced the walls of his castle. At the end of this time, he went to see the bards that sang for his father, the King, and asked them what to do.

They were three, and they spoke in fragments. ‘You should, we think,’ said the first; ‘take sackcloth,’ said the second; ‘sew swan-feathers to it,’ said the third. ‘Put it around your shoulders,’ they advised, ‘sew it to your skin. Make wings of your arms. Then when she returns, in another year and another day, join her in her domain, and she can then rejoin you in yours.’

So the prince made himself his swan-suit: and in another year and another day, he saw a dot flying out of the sun. He donned his sackcloth, biting his lip as the needle pierced his skin. Then he walked down to the edge of the water, just as she landed.

She looked at him. He knelt by the side of the lake and tried to think like a swan. Then he spread his arm-wings and flung himself into the water.

And, of course, he drowned.

March 25, 2014

by Johannes Punkt

She had brewed the tea not for fortune-telling, but because she liked the taste. She let it stand to cool, the whole pot, and forgot about it until that evening, when she had to throw the whole overbrewed thing out into the sink. In the sink the leaves looked like the viscera of something sloppily butchered, and in the language of vague shapes and omens that she and the tea spoke, it spelled out: “You cannot tell the future by boiling water and pouring it over leaves, lady.”

![]()

The robed man was trembling. He picked up a balloon-like organ from the slab and let it splat down again. He tried to look contemplative.

The suited man tapping his foot impatiently said: “Well, what does it say? I’ve got a board meeting in twenty.”

The guts of a perfectly healthy pig – healthy up until the moment the guts were outside the pig, at least – had spilled out over the stone slab dramatically. The robed man was still holding the knife. His face had paled.

Over the pig’s mouth was a gag, because the suited man had not been able to stand its squealing.

“It says, ‘augury isn’t real.’”

![]()

Ten million magic eight-balls jam halfway from “yes” to “no”. A hundred thousand stock market bots stop buying, stop selling. A thousand satellites send their last messages to Earth’s surface and become hermits.

—

guest writer Johannes Punkt, of http://zombiesintelligently.com

March 20, 2014

by Johannes Punkt

There is a flash of lightning and a hundred shipwrecks are visible at once, some awkwardly stacked on top of each other, ancient masts skewering the hulls of newer ships, and broken glass covering the entire ocean floor. Methane gas starts to seep out of the crack in a window of a building in the middle of all this, and the gas becomes bubbles and water rushes in. After a few tries, the glass yawns like an oyster and lets out all the methane it can in a great bubble and then it snaps shut again.

Inside the window, there is a room now filled mostly with water and bobbing wooden debris. The window is round, bulging, and so are the walls of the room. Where the highwatermark goes, straight like a ruler, the unescaped methane from somewhere beneath this tectonic plate takes over. Every time the ocean pressure becomes strong enough to open the crack – like squeezing a tennis ball with a slit in it – the gas is let out, and water rushes in again, and the crack grows just a little bit wider.

Over the months, the wooden debris will soak up enough water to sink to the floor and the water level will follow. The water will continue to sink through a grill-hatch down to a spiral staircase covered in patient algae, half-alive, and the water will continue sinking, trying to reach the point where the staircase ceases to be a staircase and is just a gorge, until it ceases to be a gorge and shrinks to a crack. It will sink towards this because, every so often, a bubble of gas will struggle free from the crack and travel upwards, catching itself on algae on its circuitous route up. The algae is brimming with minuscule remnants of the bubbles.

There are three sets of glassware in this tower: one massive cupola, one huge lightbulb, and one drinking glass. When the water sinks far enough, there will still be water left in this drinking glass, which stands upright on the table every time, though it’s knocked about when the water floods in. The cupola, covering the lightbulb, is filled with water too, and it takes much longer for it to dry out, and it needs to dry out completely. Sparks fly, then, and the lightbulb inside lights up for a brief few moments.

This is when the ocean squeezes the lighthouse until it opens its tiny mouth and breathes out its methane soul and lets the cold water in and everything goes dark again. Sometimes, a ship is caught in the bubble and it’s as though the sea stops existing underneath it for a good ten seconds, and the ship falls and the ocean closes around it again.

—

guest writer Johannes Punkt, of http://zombiesintelligently.com

March 11, 2014

by Artaxerxes

Lava met water. We watched. Arthur turned away. He was playing the strong, silent type. We knew he was worried.

Getting from Caerleon to Carlisle had proved unexpectedly tricky. Bedwyr had tried to climb the mast one-handed, fully armoured, had fallen into the sea, and had sunk instantly (we wished it had been Cei—we would have had time to fish him out). Uchtryd tried to rescue drowning men off the Wight, but had been dragged underwater by the weight of his enormous beard. Menw decided that he could become a dolphin and, citing Biblical verses about emergencies, tabernacles and dolphin skin, had swum out of sight using his feet as a tail. Kynedyr Wyllt had tried to pick a fight with a magical flying altar that Arthur had found somewhere, and to minimise damage to the ship we’d eventually locked both of them in the strongest part of the hold and left them to get on with it.

So, now, with Arthur, there were three useful people, apart from the shadows. We only saw them out of the corners of our eyes, pulling on ropes and making sail. We never talked about them. And now, we were here, watching fire meet water and throw up steam; and icebergs in the distance.

‘Why are we watching this?’ Arthur asked.

‘Don’t you think it’s interesting?’ we replied.

‘No,’ he said, and spoke with emphasis: ‘Why are we watching this? How did we get here?’

‘You are a border king,’ we said. ‘And this is certainly a border. Don’t you think it’s appropriate?’

‘Volcanoes? Near Carlisle?’ He stamped below as an explosion peppered our hair with ash.

In the distance, we heard snarling sounds and splintering wood as he tried to separate Kynedyr and the flying table.

March 9, 2014

by Artaxerxes

Some recent publications from the Basingstoke University Press:

- Andresson, Indo-European cthonic rituals in North Africa, translated by Velde

- Cole, The Power Stations of England: an architectural perspective

- Hague, Coniurationem Nobilitatis: how to tell genuine conspiracy theories from manufactured ones

- Koí, Teors Consibilor: a critical translation, translated by Velde

- Munnech, Ibsen and the Passing of Time

- Punkt, Recreational Near-Death-Experiences: the detriments and benefits of mushroom poisoning

- Punkt, The Middle Edda: a new translation

- Zen, Papillometrics: the butterflies of Europe and how to measure them

March 2, 2014

by Johannes Punkt

There was a desert inside her chest. We went into it. It was always daytime, and the heat rose from the ground, and sometimes stray rocks would crackle and jump like drops of oil on a skillet. There were nine of us surgeons, and two camels; by unspoken agreement we all walked. We carried with us a delicate heart inside a refrigerated box.

The shadows we cast on the desert were all the same colour as the sand that covered it. At one point, Anders picked up a handful of sand and saw that it was pieces of eggshell, white and brown, not sand at all. He knew he carried with him a silhouette of himself and he believed it to follow his movements, stretched out and wrong-angled, but now he had lost track of it. Without knowing where the silhouette ended, Anders blended into the landscape and became a tree, eggshell-coloured and leafless. This, too, was shadowless: in order to see him we had to get down on our knees or our stomachs and search for his outline protruding over the horizon.

We had used up half of our water supply, and Deirdre pointed out that this was the point to turn back. Declare it a lost mission. It had only ever had a 40% chance of working, anyway. I said, “I have a compass. Let me drag the box by myself if I have to, I will do this.” They let me have a camel, and both mine and Anders’ shares of supplies. I was grateful, and I walked quickly, afraid of hearing the hum-whirr-click of the refrigeration running out of power.

At last, I found the sun and saw my shadow dance, exalted to be there again, I think. The fiery ball was half buried in eggshell and my camel was afraid of it, stomping the ground and breathing heavily. That was the last I remember of my humped companion, it must have walked away when it realized I was paying attention to more important things.

The box still wheezed, I opened it carefully and saw everything was intact. Condensation trailed out of the box and onto the ground and sizzled away. I took off my gloves and rubbed lotion onto my hands. I put new gloves on, I removed my facepiece and took a deep breath. The very last of my water bathed my face. I took the cold heart out of the box and held it in my hands, before biting down on it. It was still beating, but slowly, pumping nothing but air, perhaps twice a minute. The blood of a twelve-year-old Parisian boy with the right blood type flowed down my chin and inside my sterile plastic suit. The last thing I remember is swallowing the last bit of meat and staring at my empty hands, wondering if I was required to lick them clean.

Then I was outside the desert again, in the room with the chequered floor, and I had just stopped moving my mouth, talking. Her parents thanked me, they knew we had done everything we could.

—

guest writer Johannes Punkt, of http://zombiesintelligently.com

March 1, 2014

by Artaxerxes

In Autumn 2012, the end of a tunnel collapsed near Durham, in the north-east of England. At the time of the accident, the only vehicle in the tunnel was a bus, the rear part of which was entirely crushed. The driver and seven passengers managed to walk away from the accident. Four of the passengers and the driver remained by the tunnel entrance, but three of the passengers immediately ran away across the fields yelling.

This would be unremarkable except that in Spring 2012, a nightclub in Berlin was struck by lightning and burned down. The compere and, again, seven other people escaped. Again, three of the people immediately ran away into the city.

To date, there have been twenty-three such incidents. The obsessive student of the unexplained is recommended to go to the website for this book, where there is a full list.

For the less assiduous, we will give details of one more of the incidents here. In 2005, in an industrial estate just outside Reading, England, an industrial centrifuge suffered spontaneous fatigue and spread shrapnel over a considerable area. The site supervisor and seven other people walked away, three of whom immediately hid in an adjoining warehouse.

In each case, police have immediately dismissed foul play, but have admitted that in each incident the three who have made a hasty exit have been the same three people.

A police spokesperson declined to name the three individuals, describing them only as “extremely unlucky”.

— Zen’s Strange but True, 2013 edition, p. 5

February 21, 2014

by Artaxerxes

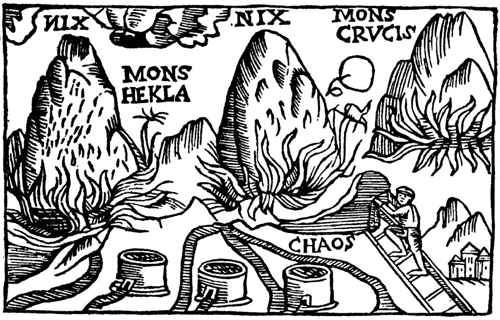

Caer Sidi is set about with lights and creatures: white lights that reflect in the water, and unheard-of hybrid animals that kneel there in silence. Its underpinnings turn every 24 hours, and bring lights and different lights to prominence.

“I saw three ships come sailing in…”

We sang an army into Caer Sidi, glorious songs, then ignominiously nipped in behind them so we could keep the open door at our backs. In the middle of the lights, in the centre of the castle itself, there was a globe, which moved. It, too, was strung with lights. Their patterns looked like the tendrils of plants, or the growth of decay on an old, old tree.

Arthur appeared again, alone, at the far door: a warlord, all too human in this inhuman place. “Tell me,” he said, “where is Caer Sidi?”

And there was a great disappearance. Some of those that had come with us just stopped and stared at the darkness all around them. A number fell upwards from the centre out towards the lights. Many were just eaten up by the sheer geometry of the place, by the perfection of the lines between the lights.

We singers survived. But, in the end, when we went with Arthur, the shining difficulty of it! Except for seven of us namyn seith none arose ny dyrreith from Caer Sidi ogaer sidi.